Respectable Western critics have long been at a loss to explain why audiences and filmmakers are fascinated by Hong Kong film. From the start, these movies have off ended guardians of taste. ~ David Bordwell

“Oh, those stupid movies!”

I was somewhat taken aback by the vehemence of my conversational partner’s reaction. A middle-aged hipster poet, he was not someone I knew well. I had rocked on up to my friend’s Christmas party a few years ago and, having no one else to talk to, had fallen into conversation with the bloke who happened to be sitting next to me on the couch. As you do, at Christmas parties. One thing led to another – the usual pleasant conversational fare was being churned through at the expected rate – when I mentioned, as I invariably do at some stage of any conversation I participate in no matter what the context or setting, that I was a huge fan of kung fu movies.

This was all a few years back, so maybe this chap said “silly” instead of “stupid”, but there was no doubt that his knee-jerk reaction was one of dismissive contempt. I was genuinely puzzled. The last DVD I had watched before trotting along to that party had been Wilson Yip’s magisterial Ip Man (2008 starring Donnie Yen at his most elegantly patrician) and my head was full of that. This film is exceptionally good; it is, at one and the same time, a hand-on-heart action-packed kung fu movie and an art-house film that transcends its own genre. It is an example of how a universally appealing story and characters, great acting, direction, and production values are not mutually exclusive to films in either genre. Ip Man was nominated for a slew of awards at the 29th Hong Kong International Film Festival and other Asian film festivals and even won some, including best film and best action choreography. It is damned classy, and about as far from the idea of a ham-fisted chopsocky as you can get.

But when I mentioned kung fu movies, this guy didn’t think of an award-winning film. He thought of something cornier, shoddier, more risible. And something vague: when I asked him exactly which kung fu movies he was thinking of, he looked embarrassed and then confessed that he had never actually watched one, of any stripe, the whole way through. “I saw half a Bruce Lee once…”

I hate Bruce Lee flicks, something which confounds Bruce Lee fans who all seem to need to lie down in a dark room after I tell them this. But the kung fu movie genre covers a vast range of sub-genres that can differ widely in aesthetic, style, and tone. Don’t like the self-conscious macho stylings of Bruce? Try the luscious romanticism of Chor Yuen’s swordplay films, with their gloriously coloured costumes, extravagant sets and dancelike high-flying action. Find them a bit saccharine? Then take on the mischief of a cracking good Lau Kar Leung film, with baroque action choreography and fun pot-boiling plots.

You know, I am rather tired of people saying, ‘Are you trying to challenge Hollywood?’ I really feel we have something quite different and equally as good as Hollywood has to offer. ~ Run Run Shaw

Chopsocky flicks have a dire reputation among most of us Westerners. The average man on the street thinks of badly made films, peopled by corny actors in silly wigs, gurning their way through formulaic plots, overlaid with dubbing so bad that it’s funny. The problem is that it is too easy, at this remove in time and place, to fall into the trap of viewing these movies with what film academics like Leon Hunt have identified as the (often white) ‘camp gaze’ – to allow cultural artefacts from different cultures some cachet only because they are different, exotic or somehow ‘other’. This is a distorted way of viewing films from other cultures and can lead to a limiting belief that ‘our’ way of filmmaking is the ultimate way, the only way. Any deviations in aesthetics or modes of performance or storytelling are seen as failures and only valued as entertainment because of their wrongness or risibility.

“Their (Hong Kong films’) audacity, their slickness, and their unabashed appeal to emotion have won them audiences throughout the world. ‘It is all too extravagant, too gratuitously wild,’ a New York Times reviewer complained of an early kung fu import; now the charge looks like a badge of honour. These outrageous entertainments harbour remarkable inventiveness and careful craftsmanship… The best of them are not only crowd pleasing but also richly and delightfully artful.” ~ David Bordwell

Of course, the martial arts movie genre has crappy movies in it; all schools of cinema do. But what many Westerners don’t understand – are not given the opportunity to see – are the many “delightfully artful” films that exist in the genre as well.

Shaw Brothers played an important part in producing movies that demonstrated that the martial arts genre can produce a lot of decent looking mainstream entertainment as well as classy art-house films. Sir Run Run Shaw set up a production process that was geared towards churning out films that were crowd pleasing. As a businessman, he wanted bums on seats and healthy box-office returns. But as a businessman who loved film and, I think, genuinely believed in it as an expression of cultural values (defined, by Sir Run Run, as the cultural values he believed in, mind), it was also important to him that Shaw Brothers films exhibited “careful craftsmanship”. Shaw Brothers’ Movietown was set up to provide the resources to support this. In this book, I look at a few directors who were able to go further in that they not only gave Sir Run Run the nicely made crowd-pleasers he wanted but were able to manipulate the resources available to them to make films that were also “richly and delightfully artful”.

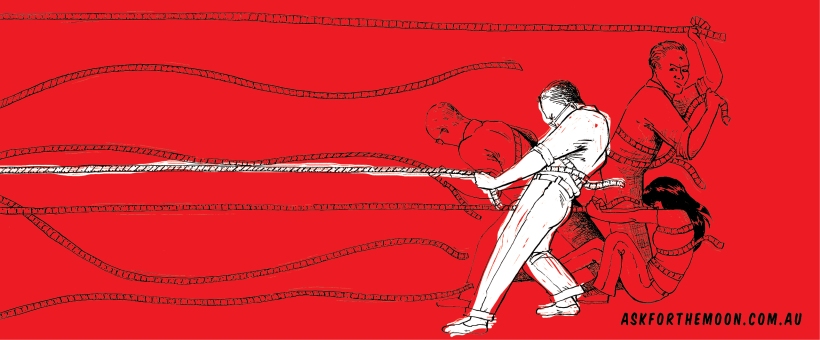

It is the tension between the artful and the operational that I want to unpack in this book. The challenge that always faced me as an arts manager – balancing the needs of the artists and the needs of the bean-counters and paper-pushers – is a challenge writ large in the case study of Shaw Brothers Studios. Examining this challenge gives deep insight into the nature of fostering innovation in an organisation.

~ From Chapter 1 of ‘Ask for the Moon’ by Meredith Lewis. Image by Rebecca Stewart.

If you would like to buy ‘Ask for the Moon: Innovation at Shaw Brothers Studios’, please go here. For more information about the book, read the media release. And you can find another extract from the book here.