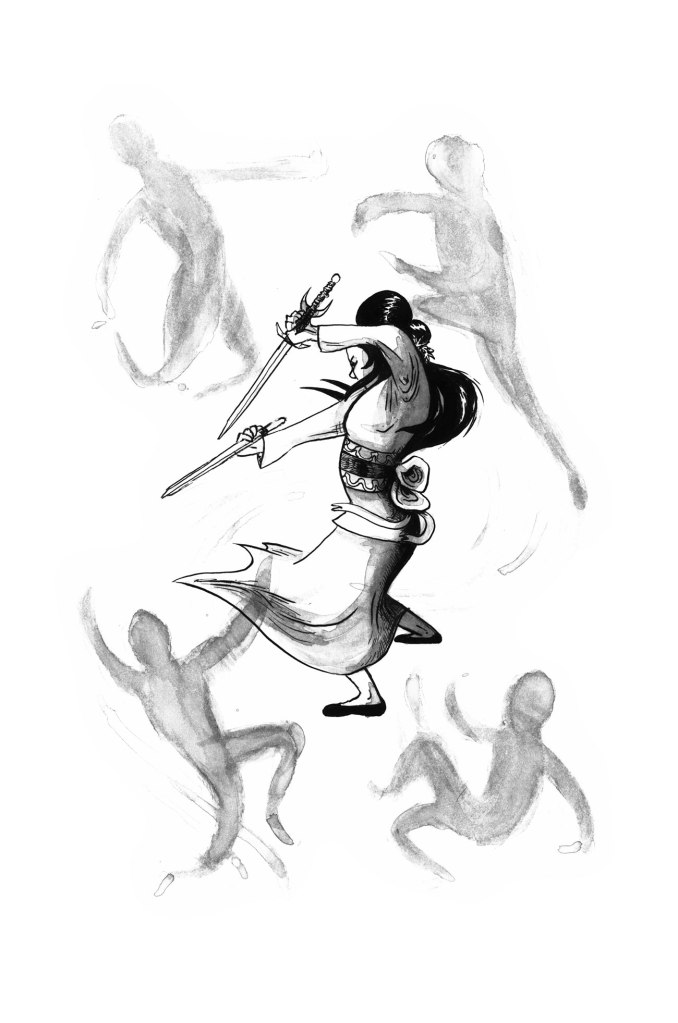

King Hu’s martial arts films both honour and innovate wuxia pian, (or Chinese martial arts swordplay films). King took certain elements long established in wuxia, and refashioned them in the films he made in the 1960s and 1970s so that they worked with an unprecedented nuance and impact.

An important convention in wuxia pian in the decades leading up to the 1960s, and one that was seen less often after the interventions of Chang Cheh and Bruce Lee, with their emphasis on hyper-macho kung fu movies, was that of the hero being a highly skilled swordswoman, and one who often had to rescue her effete male love-interest from the villains.

King Hu featured both these character types in his films, and had fun playing around with these male roles. In A Touch of Zen (1971) and Legend of the Mountain (1979), the male protagonists are scholars, lacking in martial artistry, and relying on their wits and charm instead. They are paired with, or pitted against, powerful and skilled female characters.

In Dragon Inn (1967) and The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), there are main male characters dressed like scholars, but they turn out to be expert martial artists who exploit their apparently ineffectual appearance to gain strategic advantage over the bad guys. In both these films, they collaborate with female characters who are martial arts experts and shrewd tacticians.

Even while other filmmakers were making male characters the primary focus of their movies, King Hu continued to champion the swordswoman as an important protagonist. In Come Drink with Me (1966), Cheng Pei Pei’s starring turn as the daring Golden Swallow, heroically rescuing her kidnapped brother, made her a star, and the natural magnet for whatever swordswoman roles that were up for grabs at Shaw Brothers Studios. The Fate of Lee Khan features six important roles for women, including Li Li Hua, who turns in a terrific performance as a rebel leader, ably supported by four fierce agents played by such luminaries as Angela Mao Ying, Hu Chin, Helen Ma Hoi Lun, and Polly Shang Kuan Yan Erh, who also starred as an engagingly savvy and skilled swordswoman in King’s Dragon Inn.

One of the villains in The Fate of Lee Khan is played with gimlet-eyed authority by Hsu Feng, one of King Hu’s favourite actors. She acted in all of his wuxia pian, starring in most after debuting in a bit part in Dragon Inn.

I can see why Hsu was so often used by King. Strikingly attractive, and with a strong screen presence, she always manages to impart a sense of intelligence and character in whatever role she plays. Underneath her classy exterior, there is an understated toughness that makes her turns as a martial artist believable. However, she was also an actress with a subtle range. In King’s films, she plays everything from an aristocratic sociopath, to a ruthless sorceress, to a cruelly wronged and grief-stricken daughter bent on revenge, to a thief who learns the error of her ways.

And, as much as I enjoy the many other actresses who play swordswomen in martial arts films, it’s when I think of Hsu Feng, and the different ways King Hu cast her and exploited her qualities and skills, that I can see how rich and varied the swordswoman trope could be in the tradition of martial arts filmmaking.